“Where are they taking you?” I ask him.

“I have no idea. Just cooperate with them,” he tells me as they guide him away.

None of the policemen are speaking Mongolian. They are all Chinese. Given the underlying cultural-political climate, this is not fundamentally surprising. As an autonomous region of China, Southern Mongolia (which the Chinese call “Inner Mongolia”) is set up with regional governments heavily manipulated by Chinese forces. Still, there is a discomfort in how noticeably the aura of a group environment changes when suddenly a different language dominates.

After an unresolved encounter with the police the night before, I can sense their patience has now run thin.

* * *

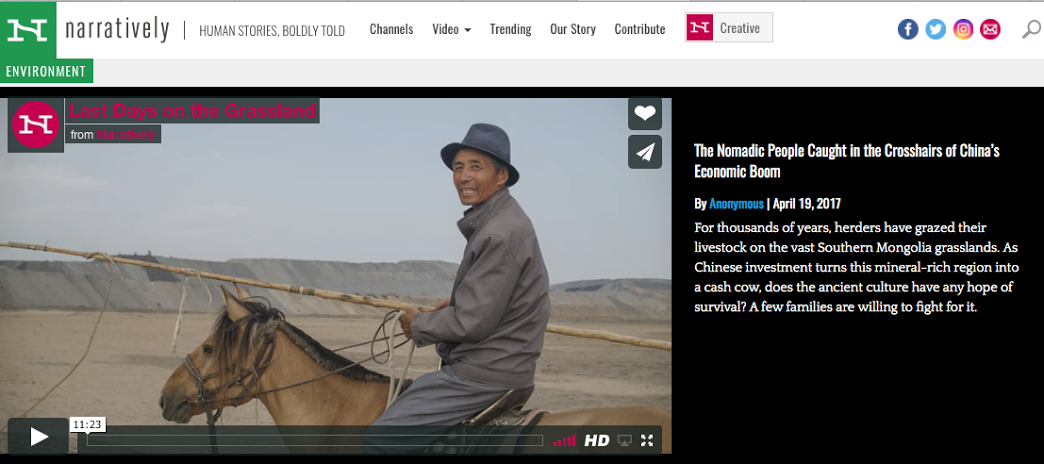

I came to the region to produce a documentary exploring the struggles of the semi-nomadic herders on this land. Memories of the pristine grasslands I had seen the last time I was there, the expansive landscapes dotted by traditional yurts and herds of livestock, remained with me as I rode this time past open pit mines, abandoned partially-finished hotels, and newly-constructed highways paved for industrial trucks. Just beneath the calm and welcoming surface of daily interactions with herders, there seemed to be a desire to speak about their changing surroundings, locked tight under a reluctant silence. What was stopping them from speaking?

Tsoguu – whose name I’ve changed here to protect him from repercussions – and I had driven over nine hours to get to Ordos. Our most recent interview subject, a leading herder activist, had put us in touch with a handful of others who were planning to head to an ongoing herders’ rights protest. Filming the protest would undoubtedly be challenging, as there’s zero tolerance for any sort of activism in Southern Mongolia. Known activists are routinely targeted for arrest at the outset of a protest in order to disrupt its confluence. Journalists and the press are blocked, and even cell-phone video is nearly impossible to capture, let alone publish effectively to government-monitored messaging boards. The frequency of protests throughout Southern Mongolia has been steadily increasing, yet media coverage intentionally fails to reflect this reality.

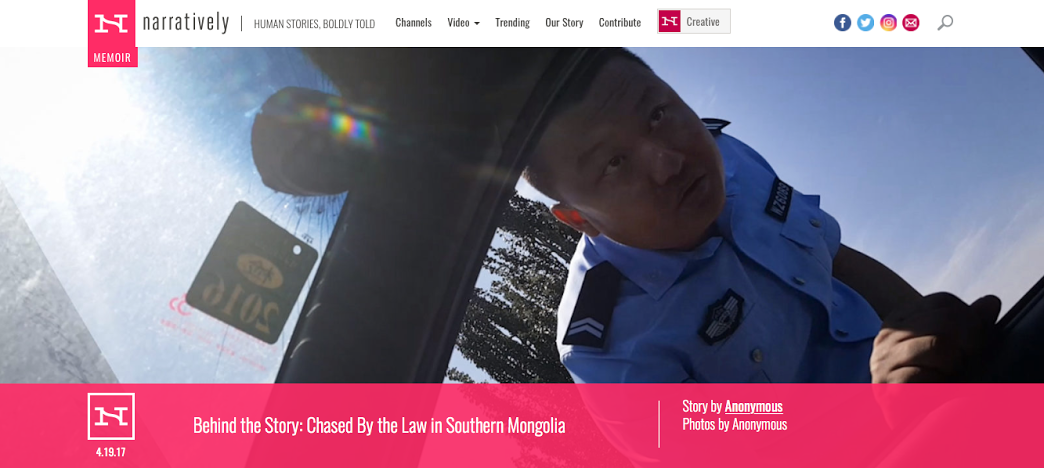

The activists picked us up along our route around four in the morning. After an hour or so of intermittent sleep in the back of their car, the expansive darkness was suddenly pierced by siren lights refracting from every angle.

The police couldn’t know for certain why we were in the car with the activists when they pulled us over. They couldn’t be sure that we even knew about the protest, and so they avoided mentioning it. Maybe we really were just hitchhiking, like we claimed. But they were suspicious.

After detaining us at a nearby precinct, the police began forming a plan. With a government highly concerned about its public image, the policemen were noticeably careful to avoid directing any accusations against Tsoguu and me. Their interactions with us, although far from subtle, attempted to maintain a facade of routine behavior. Holding Tsoguu and me overnight would be too aggressive; instead, they confiscated our phones temporarily. They didn’t bother checking my pockets, and so didn’t find my second phone. The activists were held, and the police checked Tsoguu and me into a nearby hotel around sunrise.

I woke up a few hours later to sounds of rustling as a man shuffled through my luggage at the foot of my bed.

“Tsoguu, wake up,” I said. “Who the hell is this?”

The man turned around. Tsoguu exchanged words with him in Chinese as he calmly headed out. Though poorly slept from the long drive and detainment just hours ago, I recognized the man as one of the police officials who was at the precinct.

“He says he was checking our water pipes,” Tsoguu told me, unconvinced.

We checked out of the hotel immediately. It was discomforting but not surprising that the police had been monitoring us since taking us to the hotel. But this man’s physical presence made it altogether intimidating. At the checkout desk, the hotel clerk handed us travel brochures and eagerly offered to schedule a car for us if we informed him of our plans for the day. He told us this city was boring, that there was nothing here to see or do, and so we should leave. Behind a pillar across the room, I spotted the man who had been in our room.

Tsoguu and I walked away from the hotel to hail a cab. Two vehicles followed us at walking pace. Stealth was no longer among their priorities. Tsoguu carefully explained the situation to our Chinese cab driver, uncertain of how cooperative he might be. When the light changed, he floored it, weaving through traffic, crossing to the opposite side of the road and back. The two cars caught up a few lights later.

At the next light, we crossed between traffic even more aggressively. Side streets, short blocks, left, left, right, straight, right. There was no way they could have kept us in sight. We approached a narrow alley and quickly got out of the cab. Our driver sped away.

“Your phone is off, right?” I confirmed with Tsoguu.

“Yes, but there’s still a chance they could track us if they bugged them right last night.”

If their failure to check my pockets for my second phone or their blatant manipulation of the hotel desk clerk were any indication of their meticulousness and subtlety, I figured their monitoring tactics might not be too advanced. But just then I heard two cars turning the corner, as if the world heard my thoughts and scoffed. They slowed to a stop right outside the alley we were hiding in. The men did not bother getting out of their cars. Their message was clear enough.

We hailed another cab and headed toward the city border to leave. Like escorts, the two cars continued following us, and just at the border they at last pulled us over.

* * *

Unlike our encounter the night before, today Tsoguu and I are the sole targets.

After taking Tsoguu away, a man blocks my door while a few others empty our luggage from the trunk. He then steps away and motions a Chinese woman to my window. She seems to have been getting briefed by the group of policemen nearby. She leans down and smiles at me like someone attempting to remain humble after winning a heavily sought-after prize.

“Please get out of the car, sir,” she says. “We are performing routine highway checks.”

My initial discomfort is now a sweat-inducing dread. There is nothing routine about a perfectly-fluent English speaker in Southern Mongolia. Even Tsoguu’s English is not fully fluent.

The woman at my window now awaits my response, her outwardly-gentle request leaving zero room for dispute. I step out of the car. In the dirt on the side of the road, my hard drive rests on a sheet of cloth, full of the politically-sensitive interviews I have been conducting. Most herders are hesitant to speak even amongst themselves about the oppression they struggle against. It takes very little to have a troop of policemen sent to their houses to harass and arrest them. My subjects know full well the risks involved in such interviews, but they saw no choice left but to fight the voicelessness inflicted upon their people. I fear the worst case-scenario is unfolding in front of me, as my footage seems to have landed in the most dangerous hands.

The head policeman points at the hard drive, then motions for me to follow. With a handful of other policemen and firm-faced officials, we walk seemingly without aim down some village streets. Then one of them pounds on a residence’s door. An elderly woman comes to answer. After exchanging little more than a sentence, she promptly allows them in and walks away from her home.

The police lead me in, some following behind. The head policeman points to my hard drive again, then to an outlet in the kitchen. I tell the English-speaking woman my laptop is dead and I will have to charge it. This gives me some time to think. Not so much to think of a way out, as one clearly does not exist. Time instead to think of the consequences that will follow the reveal of the interviews. Will Tsoguu and I be joining the activists from the night before, wherever they may have been taken?

My MacBook chimes.

My back faces most of the policemen. I open the hard drive then turn to exchange glances with them. The woman smiles as she has been since approaching my window. The atmosphere of their eager anticipation is visually nonexistent yet formidably palpable. Still turned toward them, my finger holds the brightness button down, dimming the screen. I hover over the main project folder. Click. Command + Delete.

“So, what kind of content would you like to see?” I ask. “I have some recent fashion work from the South of France. Also some footage from a commercial I shot in the Hamptons. Have you been to the Hamptons?”

Where this sudden audacity of mine came from I will never know. Confused after the woman translates but trying to remain outwardly unflinching, the head policeman arbitrarily points to a folder. I open some clips. An elegant woman dances in slow motion around a Vespa, playing with three large balloons. A finely dressed man stares into the lens with a vintage film camera, flashing his bulb and offering an inviting smile. I turn back around, asking if they might prefer to see something different or if they like what I am showing them. For the first time the head policeman hesitates. They all exchange glances. They seem to be reluctantly reminding themselves that there is still the chance I really am just an American tourist.

Among the increasing awkwardness, the woman’s smile gives a bit as she begins thanking me for my cooperation. On our walk back to my car, I see Tsoguu calmly leaning against the hood. The head policeman makes deliberate eye contact with me and speaks directly to me for the first time, then bows.

“We would like to thank you for your patience and we apologize for wasting your time. We hope you understand that we must perform routine security checks such as this one in order to keep Southern Mongolia safe,” the woman translates with a neutral expression.

The smile is mine now, and Tsoguu shares it as he helps me put our luggage back together. We get back on the paved highway, and soon the wide road transitions into dirt, bringing with it the familiarly comforting undulation of the grassland’s natural path. On the horizon, countless trucks pour excess sand down the growing summits of open pit coalmines.

I knew of these sorts of stories before heading to Southern Mongolia, and I sought interviews with those who had experienced government intervention in their quests for basic human rights. Hearing them in person painted a more tangible picture, but becoming a police target in the process created a sudden sense of solidarity. This is not my story, these are not my problems, yet I could now more directly understand the underlying discomfort that has become the foundation of their daily existence.

The author of this story has requested to remain anonymous so as not to jeopardize their chance of working in China in the future.

Watch: The Nomadic People Caught in the Crosshairs of China’s Economic Boom

Beyond

Great Walls: Environment, Identity, and Development on the Chinese

Grasslands of Inner Mongolia

Beyond

Great Walls: Environment, Identity, and Development on the Chinese

Grasslands of Inner Mongolia China's

Pastoral Region: Sheep and Wool, Minority Nationalities, Rangeland

Degradation and Sustainable Development

China's

Pastoral Region: Sheep and Wool, Minority Nationalities, Rangeland

Degradation and Sustainable Development The

Ordos Plateau of China: An Endangered Environment (Unu Studies on

Critical Environmental Regions)

The

Ordos Plateau of China: An Endangered Environment (Unu Studies on

Critical Environmental Regions)