| |

|

The

Independent |

|

April

5, 2013 |

|

By

Isobel Yueng -- A Chinese and reporter of China's

official news CCTV |

|

|

|

The 'tyrant China strikes

again' line isn't always applicable. We need more

perspective when looking at China's policies in the

autonomous region of Inner Mongolia

|

|

|

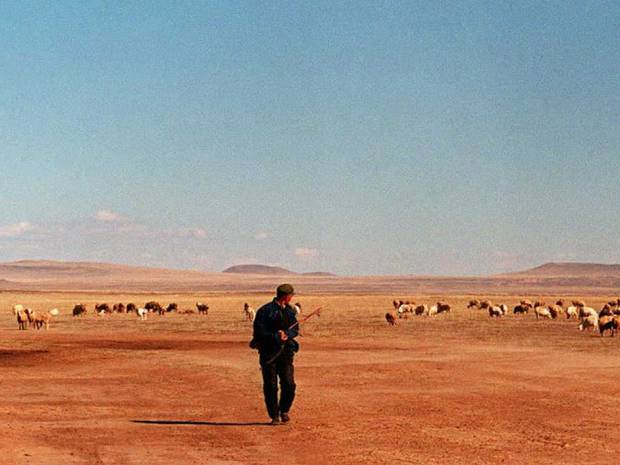

A

herdsman tends his sheep on a barren pasture, in

An Zhe Li Mu 15 October. As domestic animals in

Inner Mongolia multiply quickly, the neglected

pasture land is degenerating fast and is

expected to become a desert within several

years. |

|

China

has developed a reputation for being an unforgiving bully

towards its 55 ethnic minorities. This is hardly surprising,

given the consistently repressive policies adopted across

the allegedly autonomous regions of Tibet and Xinjiang over

the last decade. Policies pushing these outer regions into

line with the rest of China have been damned by most,

including Ilham Tohti, an intellectual from

the

Uyghur ethnic group.

He describes the situation as "worse even than colonialism".

More recently though, the

previously media-shy autonomous region of Inner Mongolia,

with a minority population of around 5 million, has started

to gain attention. In 2011, the first large-scale unrest in

two decades broke out when a Mongolian herder was killed by

a coal truck driver, and last year there was further cause

for unease when protests against land seizure were brutally

suppressed near the city of Tongliao.

Several Mongolian minority human

rights groups have sprung up abroad as a result, including

the New York-based Southern Mongolian Human Rights

Information Centre. Such groups are where most media reports

derive their information from, and it therefore becomes

tempting to draw comparisons between Inner Mongolia and

other autonomous regions, reflecting a further example of

China's apathetic approach towards its minorities.

But I'd argue that this attitude

comes from an over-simplification of Inner Mongolia's

current economical, cultural, and environmental issues. The

recent discontent has arisen due to the authorities'

enthusiastic 'recovering grassland ecosystem' policy pursued

over the last few years, where previously nomadic

minorities, including Mongols and ten other minorities

residing in the region, are seen to have been be turfed off

their land by coal-hungry Han (the ethnic group which makes

up about 92 per cent of China's population). As a result,

they are jerked in to the glare of modernity, or worse still

made into rare museum pieces lamenting the loss of their

herds and grasslands, their unwritten languages and

practical skills.

These accusations are not

unfounded, as hundreds of thousands of minorities across the

region have been forcefully encouraged to move into

permanent homes on the outskirts of Han cities. However,

it's not these cultures that the government has purposefully

set out to destroy. It's their medieval lifestyles that are

incompatible with a developing China that is exploiting coal

mining opportunities, while simultaneously attempting to

reclaim mass amounts of land. China's number one concern is

economic prosperity, and

with Inner Mongolia's rich natural

resources, it now has the strongest economic

growth of China's five autonomous regions. At the same time,

the country now faces 2.6 million square-kilometres of

desertified land, in part due to more modern and

industrialising activities from Han farmers, but also thanks

to problems of overgrazing, logging, and expanding

populations, directly linked to animal husbandry lifestyles

favoured by the minorities.

Clinging on to a minority culture is not a priority, but

that's not to say that China's aim of a homogenised standard

of living across the country is wholly bad. Reports from the

area tend to focus on relocation schemes leading to the loss

of traditional lifestyles and struggles in adapting to a

modern world. Forty-two year old Bu Lie Tuo Tian of Ewenke

ethnicity (one of the four main minorities in the region),

who I met just outside Genhe city, reflected nostalgically

on life in Shangyang Ge Qi forest before her family was

relocated. "We were freer, we could hunt and move as we

pleased, and we felt at home when we were close to our

reindeer." More reluctantly acknowledged are the severe

issues with alcoholism, and the many stories of tribe

members freezing to death and mistakenly shooting each other

whilst out hunting bears (up till last year, when their guns

were unofficially confiscated).

From a modern day perspective, at least all of the

recently relocated minority groups have seen their prospects

significantly improve since their hunting days. The

government has not only provided chalet-style housing within

a tight-knit community, electricity, monthly welfare

payments and vastly improved infrastructure, but also fresh

opportunities in the recently revamped tourism industry.

When the topic of Bu's 17-year-old son is raised, both her

and her husband Xiao Liangku are regretful that their only

child has chosen to leave his grassroots behind and move to

the city to further his education, but at the same time,

there is a strong feeling of pride. They also know that if

their son is to make his mark, he must learn Mandarin and

embrace a Han lifestyle.

Reluctance to change and grief over dying cultures are

prevalent, and as ever the media is more than eager to

criticise China's human rights policies. But it's difficult

to say that these changes have been purely negative. It

seems to me like China is stuck between a rock and a hard

place when dealing with minorities here; condemned for

dragging them into modern China, but also condemned if it

leaves them behind. Iím not suggesting that their iron fist

approach is healthy, but perhaps its time to consider that

China too wants no child left behind. |