|

Harvard

Gazzet |

|

April

5, 2013 |

|

|

|

|

|

Tumultuous times draw

history student Sakura Christmas

|

|

|

Photos by Ned Brown/Harvard Staff

Sakura Christmas, a doctoral student from

Harvard’s History Department, is wrapping up

work in the archives and libraries of Tokyo and

headed for 10 months of study in Inner Mongolia,

an autonomous region in northern China that

spans much of China’s northern border. |

|

TOKYO — To Sakura

Christmas, borders are where the action is.

They

are messy places where worlds collide: people, cultures,

sometimes armies. And the symbols of change that they

signify tell us something important about the values of the

shifting societies, about what is retained, what is lost,

and how hard people fight to retain what they have. Borders

also say much about the new societies that emerge from

tumult.

“I’m

very much interested in cultural encounters and the meetings

between different sorts of people and societies,” Christmas

said. “Some of the issues I work on now — ethnic tensions,

land rights, informal imperialism — still resonate today,

especially in China.”

Christmas, a doctoral student from Harvard’s

History Department,

is wrapping up work in the archives and libraries of Tokyo

and headed for 10 months of study in Inner Mongolia, an

autonomous region in northern China that spans much of

China’s northern border.

Christmas’ work examines a complex place at a complex time.

She’s focusing on the early part of the last century, when

Han Chinese migrant farmers pushed into Inner Mongolia, then

only thinly occupied by Mongol herders and hunter-gatherers.

The farmers’ arrival touched off a scramble for land, a

situation that became more complex after 1931, when the

Japanese invaded northern China as part of the imperial

expansion that was prelude to World War II. The Japanese

divided Inner Mongolia into two puppet states, Manchukuo and

Mengjiang.

For

herdsmen, farmers, and even Japanese imperialists, land was

an issue, whether as a resource to farm, to graze sheep and

cattle on, or to mine. Land and the policies surrounding it,

Christmas decided, would provide a useful lens through which

to view the region, the people, and the times.

“It

sounds really boring when you say ‘land tenure,’ but it’s a

reconceptualization of the understanding of land and

territory,” Christmas said. “Much of my work is on … how

imperialism affects the daily lives of people in this

period.”

Christmas has spent a lot of time in archives and libraries

in recent years. She has searched through thousands of

documents, photographing or copying those she deemed

important. Her research has taken her to three Japanese

archives and four Japanese libraries, and has her gearing up

to spend the coming months in four far-flung archives in

Inner Mongolia.

In a

way, Christmas has been preparing for her work her whole

life. With a Japanese mother and an American father who

doesn’t speak Japanese, Christmas was raised at the border

of two cultures, learning to read, write, and speak Japanese

at home while growing up and attending high school in North

Carolina.

When

she arrived at Harvard in the fall of 2003, she was hungry

to learn more about Japan and East Asia. But studying Japan

by itself wasn’t satisfying for her. Regular visits to her

Japanese grandparents had made the country familiar to her,

and not that much different from her U.S. home.

Christmas was drawn instead to the region along China’s

northern border. She spent the summer after her sophomore

year on a fellowship that had her drawing political cartoons

— she’d always had an artistic bent — for a newspaper in

Mongolia, the nation landlocked between China and Russia.

After

her junior year she took a year off to study Japanese at

Kyoto University on a fellowship funded by the Japanese

government. Despite her informal training at home, she felt

she needed to improve her Japanese reading and writing

skills if she was to conduct research in the language.

|

|

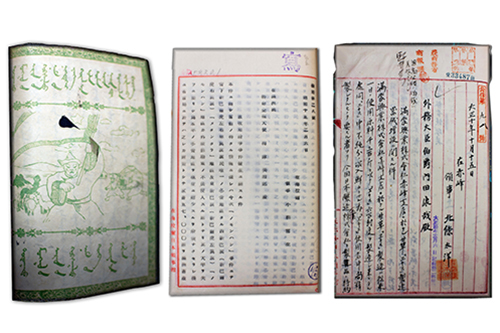

| Three documents

unearthed by Harvard doctoral student Sakura

Christmas during research at archives in Tokyo.

Christmas is conducting historical work there

and in China to shine light on the Japanese

empire’s expansion into China. Click on the

audio clips below to hear Christmas discuss the

documents and their significance to her work. |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

On her

return to Harvard, Christmas did her senior thesis on

Japan-occupied Manchuria, an area in Northeast China

encompassing part of Inner Mongolia. After graduating, she

spent a year teaching English in another part of China,

Xinjiang, an autonomous region north of Tibet, with the

nonprofit group Princeton in Asia. Christmas was there when

deadly rioting broke out in the restive region, and grew

concerned when some friends got caught up in it, though

thankfully they were unharmed.

Mark Elliott, the Mark Schwartz Professor of Chinese and

Inner Asian History, advised Christmas on her senior thesis

and later became, with Associate Professor of History

Ian Miller, an adviser on her doctoral thesis.

Elliott, who’s known Christmas for seven years now,

described her as energetic and cheerful, a good student who

works hard and takes advice, but who also has the ability to

balance advice against her own instincts. After receiving

her undergraduate degree, for example, Elliott knew

Christmas wanted to teach for a year in China. Since she was

interested in Manchuria, he suggested she go to Dalian, a

port city with clean air and a fascinating colonial history,

where people were known for having more liberal attitudes.

“Instead, she opted for Shihezi, a bleak oil town in

northern Xinjiang, where among her colleagues at the

university were Han intellectuals ‘exiled’ from teaching

posts in China proper,” Elliott said. “The increased tension

between Han and Uyghur populations in Xinjiang she witnessed

during her stay — which ended in street violence in Urumqi

in summer 2009 — made for a challenging year, to say the

least. But I’m sure she learned more from those experiences,

difficult as some of them were, than she would have had she

chosen the more comfortable environment.”

Christmas started her doctoral work in the fall of 2009 with

an idea of the time and place she wanted to study. Elliott

and Miller helped her settle on land as a focus for her

interest in the region.

“I

could narrow down the time, and roughly the place,”

Christmas said. “I knew I wanted to work on the borderlands

region in China and narrowed it down to the Japanese

occupation.”

In

addition to Japanese imperial policies and the day-to-day

use of land by herders and farmers, the emerging role of

science in measuring and analyzing land is also important,

Christmas said, so her work will include an examination of

the role of science, as well as environmental aspects such

as desertification from careless use.

“In

the broadest terms, she’s bringing the history of science

and environmental history together in a study of the

Japanese empire and its edges,” Miller said. “We have ample

studies about how empire functioned in colonial cities and

so on, but before Sakura we had little sense for what the

Japanese empire looked like from its edges. This is an

empire that, at its peak, reached from the Aleutian Islands

to Indonesia, from Pacific atolls to the steppes of

Manchuria and Mongolia. It is this last area that has

attracted Sakura’s attention, and it is among the least

studied components of the Japanese imperium, despite its

obvious strategic and economic importance.”

When

asked about key moments in her work, Christmas talks about

unearthing documents like the record of the 58,000 head of

livestock the Manchukuo puppet government bought from Mongol

herdsmen after losing a 1939 border battle with the Soviet

Union. The loss shifted the border, placing the herdsmen’s

winter grazing grounds in the Soviet Union. The Manchukuo

government decided it was better to pay for the sheep and

cattle than have people fighting over the grazing lands that

remained, but Christmas said that decision ignored the

central role that livestock played in the lives of

traditional herdsmen.

“For

me, they’re huge, but in the grand scheme of things, they’re

all very small eureka moments,” Christmas said of that and

other archival finds. “One thing I like about the archives

instead of the libraries is that there’s a surprise every

day. You have to recalibrate every day based on the

documents you find that day and how they’re going to change

your dissertation and the arguments you want to make.”

For

example, Christmas was originally going to include a chapter

on opium cultivation, but found that, because it is illegal,

people didn’t want to talk about it and documents were hard

to find. After turning up references to licorice extraction,

she substituted licorice for opium, as the story of licorice

in the region allowed her to cover much the same ground.

Licorice is found in the deep roots of the plant and its

harvest, if done carelessly, can lead to desertification in

a fragile, dry environment. In addition to environmental

impacts, Christmas will also examine the contrast of

licorice’s pre-invasion use as a traditional Chinese

medicine — used in root form for upset stomachs — and the

more industrial processing by Japan, which extracted the

essence from the roots and shipped it for use in soy sauce

and tobacco products.

As

Christmas was wrapping up her Tokyo research in late

February, she was looking forward to her stay in Inner

Mongolia. Practical concerns were for the moment trumping

worries about her research, as she still didn’t have an

apartment lined up and was hoping a teacher’s apartment

would become available.

While

the prospect of traveling alone to a place unfamiliar to

many in the United States might seem daunting to some, it

was something Christmas had done before. In fact, she was

anticipating getting some open time to begin writing while

she waited for permission to visit archives in the regional

capital of Hohhot and in the towns of Hailar, Qiqihar, and

Chifeng.

“Many

of these border regions [in the study area] are now settled,

but there are similar issues taking place in China today,”

Christmas said. “It may be the way Asia might be headed,

especially if we forget the past. History is never dead.” |